"Conservatives don't want to scrap the Human Rights Act. We want to replace it with a British Bill of Rights".

So states Tim Montgomerie. Before quoting: "Conservatives never seem to understand the importance of language as much as their Labour opponents do".

I don't think it matters what language is used to advocate getting rid of the HRA 1998. In my view, there are some wrongs with the HRA. However, replacing it appears to me to be extremism. I think the HRA can be improved with simple amendments. It is xenophobic nonsense to seek to replace it with a British Bill of Rights. Civil rights are not quite the same as human rights. As the title explains Universal Declaration of Human Rights is about human rights which are universal, rather than rights solely British, French or German, for example. It forms part of The International Bill of Human Rights. Therefore, a British Bill of Rights appears to me to be totally superfluous to our requirements. Furthermore, the European Convention on Human Rights was in part drafted from the Bill of Rights 1688/9, which is, of course, British!

I suspect that what Tim Montgomerie is really saying is that the spin, lies, used by the Tory party is not being swallowed by the general public. Therefore, he is suggesting that the language is altered to dress up the real meaning with better camouflage. If this is the case then people will need to be very suspicious of those seeking to remove human rights from the electorate. It is the sort of thing a tyrant would do. When a totalitarian or authoritarian state seeks to remove human rights it is only for one reason, to abuse its citizens.

David Cameron's war against human rights is as stupid as George Bush's war against terror. He is getting jittery as the 11 October deadline approaches to bring forward proposals to amend the law to allow convicted prisoners the vote. It is dishonest of him to talk about a social fightback like is happening in Libya. There it is the people against the regime. With Cameron he is against the people deserving of human rights.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

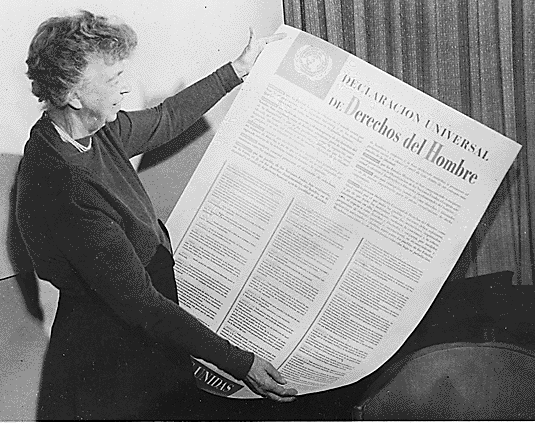

Eleanor Roosevelt with the Spanish version of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Eleanor Roosevelt with the Spanish version of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (10 December 1948 at Palais de Chaillot, Paris). The Declaration arose directly from the experience of the Second World War and represents the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are inherently entitled. It consists of 30 articles which have been elaborated in subsequent international treaties, regional human rights instruments, national constitutions and laws. The International Bill of Human Rights consists of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its two Optional Protocols. In 1966 the General Assembly adopted the two detailed Covenants, which complete the International Bill of Human Rights; and in 1976, after the Covenants had been ratified by a sufficient number of individual nations, the Bill took on the force of international law.

European Convention on Human Rights

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (commonly known as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)) is an international treaty to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe. Drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, the convention entered into force on 3 September 1953. All Council of Europe member states are party to the Convention and new members are expected to ratify the convention at the earliest opportunity.

The Convention established the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Any person who feels his or her rights have been violated under the Convention by a state party can take a case to the Court. Judgments finding violations are binding on the States concerned and they are obliged to execute them. The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe monitors the execution of judgments, particularly to ensure payment of the amounts awarded by the Court to the applicants in compensation for the damage they have sustained. The establishment of a Court to protect individuals from human rights violations is an innovative feature for an international convention on human rights, as it gives the individual an active role on the international arena (traditionally, only states are considered actors in international law). The European Convention is still the only international human rights agreement providing such a high degree of individual protection. State parties can also take cases against other state parties to the Court, although this power is rarely used.

The Convention has several protocols. For example, Protocol 13 prohibits the death penalty. The protocols accepted vary from State Party to State Party, though it is understood that state parties should be party to as many protocols as possible.

History

The development of a regional system of Human Rights protection operating across Europe can be seen as a direct response to twin concerns. First, in the aftermath of the Second World War, the convention, drawing on the inspiration of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights can be seen as part of a wider response of the Allied Powers in delivering a human rights agenda through which it was believed that the most serious human rights violations which had occurred during the Second World War (most notably, the Holocaust) could be avoided in the future. Second, the Convention was a response to the growth of Communism in Eastern Europe and designed to protect the member states of the Council of Europe from communist subversion. This, in part, explains the constant references to values and principles that are "necessary in a democratic society" throughout the Convention, despite the fact that such principles are not in any way defined within the convention itself.

The Convention was drafted by the Council of Europe after World War II in response to a call issued by Europeans from all walks of life who had gathered at the Hague Congress (1948). When over 100 parliamentarians from the twelve member nations of the Council of Europe came together in Strasbourg in the summer of 1949 for the first ever meeting of the Council's Consultative Assembly, drafting a "charter of human rights" and creating a Court to enforce it was high on their agenda. British MP and lawyer Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, the Chair of the Assembly's Committee on Legal and Administrative Questions, guided the drafting of the Convention. As a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials, he had seen first-hand how international justice could be effectively applied. With his help, French former minister and Resistance fighter Pierre-Henri Teitgen submitted a report to the Assembly proposing a list of rights to be protected, selecting a number from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights just agreed to in New York, and defining how the enforcing judicial mechanism might operate. After extensive debates, the Assembly sent its final proposal to the Council's Committee of Ministers, which convened a group of experts to draft the Convention itself.

The Convention was designed to incorporate a traditional civil liberties approach to securing "effective political democracy", from the strongest traditions in the United Kingdom, France and other member states of the fledgling Council of Europe. The Convention was opened for signature on 4 November 1950 in Rome. It was ratified and entered into force on 3 September 1953. It is overseen by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, and the Council of Europe. Until recently, the Convention was also overseen by a European Commission on Human Rights.

Drafting

The Convention is drafted in broad terms, in a similar (albeit more modern) manner to the English Bill of Rights, the American Bill of Rights, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man or the first part of the German Basic law. Statements of principle are, from a legal point of view, not determinative and require extensive interpretation by courts to bring out meaning in particular factual situations.

No comments:

Post a Comment