Tom Stoate, guardian.co.uk, Thursday 21 April 2011 15.27 BST

In countries where capital punishment has been banned the alternative can be inhumane life imprisonment without parole

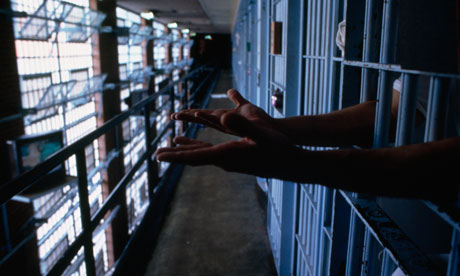

No parole … 'The abolitionist's goal should be a humane, proportionate response to perpetrators of serious crime.' Photograph: Andrew Lichtenstein/Sygma/Corbis

No parole … 'The abolitionist's goal should be a humane, proportionate response to perpetrators of serious crime.' Photograph: Andrew Lichtenstein/Sygma/CorbisAmnesty International's recently published death penalty statistics hailed a "decade of progress".

For opponents of capital punishment, this annual tradition of significant documented falls in executions is a victory – of sorts. As Amnesty reported, of the 67 countries that handed down death sentences in 2010, only 23 actually carried out executions. These statistics, however, do not tell us this: what happened to the prisoners who escaped state execution in the remaining 44?

Very little attention is given to the sanctions that should replace capital punishment, or to what happens after it is abolished. Consider Uganda. A landmark legal challenge in 2009 abolished mandatory death sentences for certain crimes. But the Ugandan criminal justice system was unprepared for the change. Under pressure from politicians facing a backlash from a public highly supportive of capital punishment, and in the absence of any new sentencing guidelines, judges handed down draconian prison sentences instead – including life without parole, previously nonexistent in Uganda.

The attraction of life without parole, now the commonest alternative to capital punishment, is understandable. It allows governments to claim they are protecting the public by permanently removing serious offenders from society. It appeases public outcry at the early release of dangerous convicts on parole. And it means abolitionists can show they are not soft on crime, while at the same time eliminating the danger of executing innocent people. But life without parole trades one severe punishment for another: execution is swapped for a protracted, hopeless death in unspeakable conditions. HIV rates in Ugandan prisons are more than double the rest of the population. In Malawi, where no one has been executed since 1992, prisons are vastly overcrowded and rife with infectious disease; prisoners are denied contact with families, and sexual and psychological abuse by inmates and guards is routine.

Across the world today, those lucky souls who escape death by hanging, beheading, electrocution, lethal injection, shooting or stoning live out their lives in conditions tantamount to a breach of international prohibitions of cruel and inhuman punishment, as an emerging jurisprudence recognises. Whole life imprisonment can also be a form of legal disappearance. In 2009, after Kenya's last elections , some 4,000 prisoners had their sentences commuted to life to without parole by President Kibaki. Some of those prisoners – living in some of the world's most crowded and worst funded prisons – have not been heard from since, by their lawyers or families. These are hardly arguments for retaining capital punishment. But if a sentence of 75 years, with hard labour and without review or hope of release – the current alternative in Trinidad and Tobago – is considered a "victory", it is surely time to rethink our indices of success.

Amnesty, for its part, does not propose any particular substitute, other than opposing alternatives that constitute degrading punishment. In Death Penalty: Questions and Answers, Amnesty rightly highlights the brutalising effect of state execution, the cost, the travesties of justice, its disproportionate use against poor and minority communities, its negative impact on victims' families. But Amnesty fails to challenge itself with the most crucial questions of all: "What alternatives do you propose, and how can we convince governments to implement them?"

On the one hand, Amnesty is right not to preach. Finding affordable and publicly acceptable alternatives in desperately underfunded prison systems is an enormous challenge. Overwhelming majorities – including in Britain – support capital punishment, often under the influence of misleading statistics on the deterrent effect of the death penalty and unproven links between serious crime and capital punishment. And in the absence of decent victim support services, it becomes convenient for supporters of capital punishment to exploit crime victims' grief, arguing that they will settle for nothing less than ultimate retribution or alternatives that do not involve throwing away the key.

Yet Amnesty's neutrality among alternatives is symptomatic of a wider problem: who will tackle the way the criminal justice system operates in countries that retain the death penalty? Politicians are reluctant to expend scarce resources or political capital on properly rehabilitating unpopular and vilified groups of prisoners.

A lawyer's work, meanwhile, is done once their client's death sentence is commuted. Few headlines focus on the aftermath, and few international advocates jet in to ensure that those released from death row are not tortured in prison, contract tuberculosis or HIV, lose contact with their families or die in appalling squalor. Indeed, litigation can often cause unintended harm. In the United States, as Peter Hodgkinson of the Centre for Capital Punishment Studies (one of few organisations raising this issue) has pointed out, a government backlash against death-penalty litigation has directly or indirectly led to an increase in the number of capital crimes, and to severe restrictions in the appeal process.

Life without parole cannot be the alternative. Both the UN and Council of Europe guidelines on managing long-term prisoners recognise that very small numbers of convicted prisoners may have to stay in prison for their natural lives – but only with regular reviews of their risk of reoffending. Some states refuse to extradite suspected offenders to countries where they might face a whole-life tariff. And in Europe, as Edward Fitzgerald QC has noted, there is growing legal recognition of the capacity for redemption and rehabilitation – and that "any sentence that effectively closed the door for ever would be contrary to Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights prohibiting cruel and inhuman treatment or punishment". Three British whole-life prisoners are currently challenging their sentence in the European Court of Human Rights on those grounds.

The abolitionist campaign's goal should be a humane, proportionate and human rights-compliant response to perpetrators and victims of serious crime. It might require global guidance to standardise the huge, and often grossly disproportionate range of sentencing decisions. It will certainly require building and sustaining capacity among lawyers to challenge human rights abuses in prison, and training police and prison staff to cope in effective and positive ways with serious offenders. It will also mean recognising that the high proportion of mentally ill prisoners on death row might be better dealt with in clinical rather than punitive settings.

And as for the most serious crimes of all, those against humanity? Compare the approach of post-apartheid South Africa, where many offenders took part in the truth and reconciliation process rather than receiving punitive sentences, or the participation by perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide in community service and open dialogue with victims, to the grisly spectacle of Saddam Hussein's execution.

A falling execution rate is not the only measure of rising humanity. We cannot simply declare victory when capital punishment is removed from the statute book, or when fewer prisoners are executed. Moving to a humane penal response to serious crime, in societies in which the death penalty has flourished for centuries, cannot be done at a stroke. The entire abolitionist project is undermined if wholesale infrastructural change is not addressed. Too often, current alternatives to the death penalty raise the uncomfortable question: "what would you rather?" Those that do not are not easy – but silence does no justice to our cause.

• This article was written with the assistance of Professor Peter Hodgkinson and Kerry Akers at the Centre for Capital Punishment Studies

No comments:

Post a Comment