Mystery files cast doubt over verdict on Robert Magill gangland killing

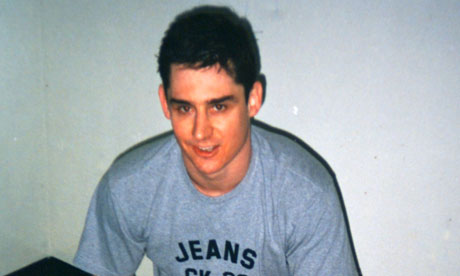

Kevin Lane has been in jail for 16 years after being found guilty of murder. But did police pervert the course of justice?

Kevin Lane has served 16 years for murder but maintains his innocence. Photograph: Martin Argles for the Guardian

It was a notorious killing carried out one morning in a Hertfordshire backwater. Two men had approached Robert Magill as he walked his dog close to his home in Chorleywood on 13 October 1994. One of them was seen by several witnesses to pull out a shotgun and shoot Magill five times at point blank range. The final shot was delivered to the head as Magill lay prostrate.

As of today, Kevin Lane will have served 16 years and 255 days of a minimum 18-year sentence for carrying out what was seen as a classic contract killing. Lane was raised in the criminal underworld, but has always claimed he was innocent of this crime.

Many aspects of the case remain troubling and new evidence now threatens to blow apart not just Lane's conviction but the way in which it was achieved.

The Observer understands that a specialist team reporting to the Crown Prosecution Service is examining whether a clutch of confidential internal police files, apparently relating to the case and sent anonymously to Lane's lawyer, Maslen Merchant, are genuine.

The files, which have been seen by the Observer, appear to be copies of secret memos sent between a number of police officers involved in the case. For legal reasons, the evidence cannot be reproduced at the moment. But, if genuine, Lane's lawyers believe it would have a material effect on their client's appeal.

In their submission filed before the Court of Appeal, the lawyers claim the documents, "if genuine, demonstrate the most blatant, deliberate and… shocking, plot by police to pervert the course of justice and ensure the applicant's conviction for murder".

They would also illuminate the shadowy way in which the judicial system prosecuted contract killings, often having to go to great lengths to protect police sources who helped to secure convictions but were themselves closely connected to the criminal underworld.

Central to the prosecution case against Lane was his palm print, found on a plastic bin liner in which the murder weapon was said to have been carried. The liner was found in the boot of a car Lane admitted driving. Another article in the car's boot was tested and found to have traces of nitroglycerine on it, indicating the presence of a weapon.

Lane, who had travelled from Spain two weeks before the killing under a false name, claims he was at home at the time of the crime, but accepted he had borrowed the car about a week before the murder. His son's fingerprint was also found in the car, reinforcing Lane's claim that he had used it to ferry his family around.

A defence expert suggested the apparent presence of nitroglycerine could have come from an industrial nail gun. Lane said he had entered the country under a false name because the Department for Social Security had been after him in connection with a benefit claim.

But for Lane's supporters, the most troubling aspects of his case centre on the secrecy that has characterised it. Some evidence disclosed at Lane's retrial in 1996 was subjected to a public immunity interest order, meaning it was not shared with his legal team. For years, Lane's lawyers sought to establish the full contents of the suppressed material, who had authorised it, and why.

The new material, if genuine, answers many of their questions. Lane first stood trial in October 1995 with Roger Vincent, who was found not guilty of participating in Magill's murder by direction of the judge. A hung jury was unable to return a verdict on Lane.

Since Lane's conviction at his second trial, evidence has emerged showing Vincent had lengthy discussions with police officers shortly after his arrest. Statements shared with Lane's legal team by a detective sergeant, Christopher Spackman, also confirmed that Spackman had visited Vincent while he was on remand in HMP Woodhill.

Spackman was later jailed for conspiring with others to steal £160,000 from Hertfordshire police, money the married father of three paid into his lover's account.

The prosecutor at Spackman's trial claimed: "The lengths he went to, the lies he told and the documents that were forged would have been worthy of a seasoned fraudster."

Spackman's name also surfaced in a 2005 court of appeal case that quashed the conviction of two men, Nazeem Khan and Cameron Bashir, in a case involving credit card fraud. The court had heard Spackman had displayed "an ability to conduct complicated deceptions within a police environment".

On his website, Lane makes the extraordinary claim that before his first trial had finished, Spackman had visited Vincent's mother and told her that her son was coming home, but "Lane" would be found guilty. Spackman had also visited Vincent's mother's home twice after her son had been released.

Vincent sued Hertfordshire police for false imprisonment after his acquittal for the Magill killing. He alleged Spackman had offered him a deal to drop the case against him and pay him a reward if he turned Queen's Evidence. Spackman later insisted it was Vincent who had approached him to "do a deal".

It was not to be Vincent's last brush with the law. In August 2005 he and his friend David Smith were convicted of the 2003 killing of David King, who was shot 26 times with a Kalashnikov outside his gym in Hoddesdon, Herts.

Logs later released by the police showed that during the original Magill murder inquiry they had received more than 20 tip-offs claiming Vincent and Smith had been responsible. They were well known in the criminal world and were suspected of having carried out several killings.

Lane's lawyers believe that charting the relationship between Vincent and Spackman is crucial to the success of his appeal. The relationship certainly pre-dated the Magill murder. In 1992, it was Spackman who had liaised with Vincent when he gave evidence in the case of a man convicted of attempted murder and false imprisonment. Vincent received a commendation from the judge for his bravery in testifying.

Today Vincent is behind bars and refusing to shed light on the extent of his relationship with Spackman. Lane continues to protest his innocence from a category B prison, potentially putting his release date in jeopardy.

His hopes now rest on whether the internal police files mysteriously posted to his lawyers are real or sophisticated forgeries. Given the bewildering twists and turns in Lane's case, either conclusion is possible.

No comments:

Post a Comment